Legendary Italian designer Giorgio Armani has died at 91 in his home in Milan. Born in 1934 in Piacenza, Italy, Armani founded his eponymous luxury fashion house in Milan in 1975. Today, Giorgio Armani is an empire, from makeup to home decor, worth over $10 billion. Armani’s personal net worth is estimated even higher, at some $12 billion.

Armani leaves a legacy that spans generations, genders and socioeconomic strata.

Known for his relentless work ethic, Armani remained president, chief executive and sole shareholder of his company until the day he died. By all accounts, his executive involvement at Giorgio Armani was not just in name, but also in action. “Indefatigable to the end, he worked until his final days, dedicating himself to the company, the collections and the many ongoing and future projects,” an official statement from his company read.

Armani secured his place in fashion history in 1980 by providing the wardrobe for actor Richard Gere in the neo-noir crime drama “American Gigolo.” Armani’s tailoring, fluid and soft, without the then-customary shoulder pads and heavy construction, defined the film and then defined menswear for the decade.

Armani leaves a legacy that spans generations, genders and socioeconomic strata. For most, he is the name on their favorite bottle of perfume. For celebrities, he is the standard-bearer of red carpet gowns. For fashionable men, he revolutionized and reshaped the suit. For millennials, he created the defining foundation of the full-glam makeup era. And, perhaps most crucially, for high-powered career women, from Hollywood to Washington, he was the arbiter of the women’s suiting.

Fittingly, it was Diane Keaton, now synonymous with perfectly executed menswear, who was the first to wear Armani on the red carpet. In 1978, Armani dressed Keaton in a deconstructed cream blazer and striped skirt to accept her Oscar for “Annie Hall.” Armani reflected on the moment in a 2020 interview with Grazia: “Women were discovering a new voice as professionals. I found myself the designer credited with giving these women an appropriate wardrobe — something that could compete sartorially with what their male colleagues were wearing. Diane is channeling that spirit with this outfit.”

That spirit, as it were, is still very much felt for women in politics. Much has been made, including by me, about how women lawmakers are unfairly and harshly judged for their sartorial choices compared with their overwhelmingly male counterparts.

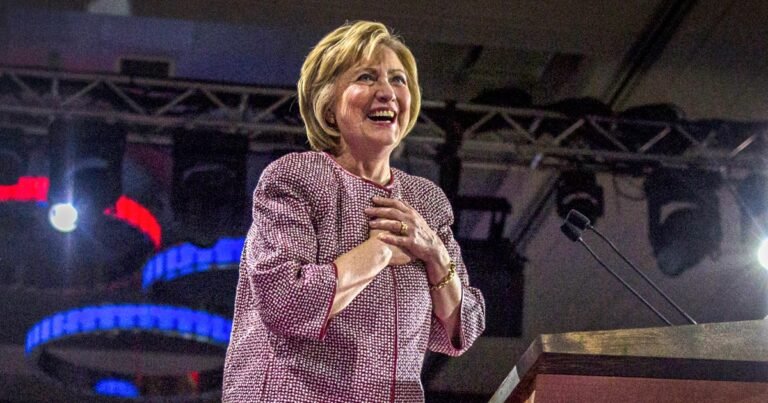

Hillary Clinton, for example, was subjected to relentless criticism for her clothing choices over her illustrious career, including, at one point, for a costly but beautiful Armani jacket. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, the former House speaker, also with a longtime proclivity for Armani suits, has been the subject of a number of think pieces evaluating her wardrobe and the cost of it. Armani has dressed decades of women in Washington.

Suiting wasn’t always de rigueur for women in Washington. In what was called the “Pantsuit Rebellion,” then-Sens. Barbara Mikulski of Maryland and Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas were the first two sitting women lawmakers to wear pants on the Senate floor. Their small rebellion led to a 1993 rule change permitting pants for women in the Senate. Legend has it that both Mikulski and Kassebaum wore Armani suits. Even if that isn’t true, and I promise I would say this even if Armani hadn’t just died, it is utterly conceivable, not just because of Armani’s popularity, but also because of what his suiting represents for women.

The point is not to look like a woman in a man’s suit but to look like a woman in a woman’s suit.

Consider the subversive nature of a woman’s Armani suit: beautifully constructed, well-executed, indisputably fashionable but intentionally resistant to the sort of “flattering” defined only by a patriarchal lens. Armani suits are deliberately powerful, not precious. A well-executed suit for a woman in politics isn’t a mimicry of a male colleague’s masculine separates. The point is not to look like a woman in a man’s suit but to look like a woman in a woman’s suit.

Armani’s relevance in the political realm isn’t limited to just the United States: Italy’s first woman prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, frequently wears Armani. A controversial, Trump-aligned, conservative-leaning populist, Meloni began her term in dark Armani suits, even, according to The New York Times, posing for her official state portrait in Armani. Meloni’s fashion choices, like those of her American counterparts, are scrutinized. The choice to wear a celebrated Italian brand as an Italian head of state is, of course, entirely by design.

For women in power, those sitting in boardrooms, walking red carpets and standing inside the Capitol, Armani’s pioneering design has helped to provide necessary strength, professional identity and authority for nearly five decades. If dressing is a shield, then an Armani suit is a full set of armor.