By Helen Miller and Michael Strand

This show demonstrates how Beauford Delaney absorbed lessons from modernism in order to create a unique abstract style that remained committed to representation.

Beauford Delaney’s works on paper on exhibit at The Drawing Center in NYC until September 14, might come as something of a revelation, for a number of reasons. There is the range of Delaney’s work, his incredible life story, and what the show tells us about his development as an artist. Delany is considered by many to be an “artist’s artist,” and a persistently neglected one at that. In the Medium of Life demonstrates how he absorbed lessons from modernism in order to create a unique abstract style that remained committed to representation.

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee at the end of 1901, Delaney’s life and work took him to New York and Paris, but also Boston, where Delaney came in the early ’20s to study art. While not formally enrolled in art school, he took classes at several schools in the Boston area at the time. He left for New York in 1929, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance. Delaney straddled Harlem and bohemian Greenwich Village, where he lived on Greene Street, becoming particularly close to Countee Cullen (the “poet laureate” of Harlem) and Georgia O’Keeffe, in addition to the writer Henry Miller. Most famously, Delaney met James Baldwin in New York and, eventually, at the urging of his younger friend, repeated Baldwin’s own expat move, leaving for Paris in 1953. There Delaney would spend the rest of his life—his tomb, unmarked until not long ago, can be found in the Cemetery of Thais.

Given his life trajectory, Delaney’s work has been given a mostly biographical treatment to date. This show deepens that perspective. But what also becomes clear is that Delaney’s artistic practice is not reducible to his life story. For all that his art engages, and battles against—-racism, homophobia, alcoholism, and mental illness—-it also cultivates a heroic separation from those brutal realities.

As early as his time in Boston, Delaney’s interests tended to split between two modes of painting. When exploring the Museum of Fine Arts and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, he was drawn as much to John Singer Sargent’s portraits as to Claude Monet’s landscapes. Delaney’s early work in portraiture can be situated within the Harlem Renaissance and “the New Negro” project, named after philosopher Alain Locke’s 1925 anthology of the same name and its call for an artistic reclamation of Black identity.

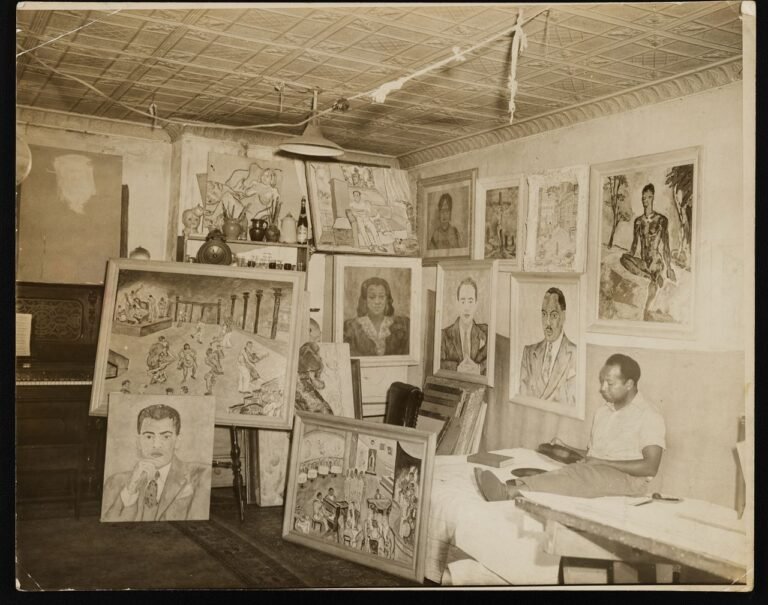

Photograph of Beauford Delaney in his NYC Studio, 1940. Photo: Betsey B. Creekmore. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Delaney’s New York period also shows the influence of his friend Stuart Davis and the latter’s jazz-influenced nascent brand of pop art, which featured bold, brash, and colorful street scenes. They are riffs on the Ashcan School, particularly its politically engaged portrayal of daily life in the city. Yet, at this stage in Delaney’s career, the years right before he left New York, his vision seems to have been limited — it is as if Delaney was trying on a style that didn’t quite fit. Baldwin observed, wisely, that Delaney’s paintings underwent the “most striking metamorphosis into freedom” after his friend’s arrival in Paris. Chartres (1954), the first piece in The Drawing Center show, is emblematic of that transformation: its use of outline resembles Delaney’s earlier street scenes, but that sits in tension with a new embrace of non-figurative shapes and free-er mark making.

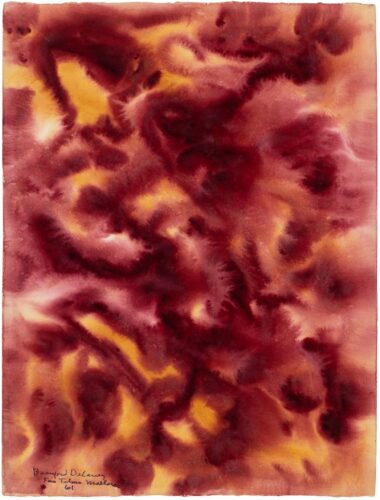

Beauford Delaney, Untitled, 1961. Watercolor on paper

Photo: The Drawing Center, NYC

In two Untitled watercolors on paper from 1961, Delaney’s continued interest in abstraction fuels a brilliant portrayal of light—swarming, swirling, pushing through. The layering in the work’s visual effect suggests a freeze-frame of ink dispersing in water, producing an analogue (as some critics have noted) with Rorschach tests. The resonance is feasible: these works might be an expression of Delaney’s inner tumult and his triumph over it. But, as with Rorschach tests, such a connection is beguilingly abstract; these look to be chance forms, abstract representations.

The abstract style Delaney arrived at may have links with abstract expressionism, but it also distinguishes itself from that American art movement. The scale or action of his abstract images are less prominent than their density and sensitivity. The artist’s human, portrait-sized drawings in this show have depth: they are gestural but worldly, maintaining a connection to the movements of the painter’s wrist. They do not embrace the self-enclosed “flatness” that critic Clement Greenberg famously found emblematic of all modernist painting, particularly abstract expressionism.

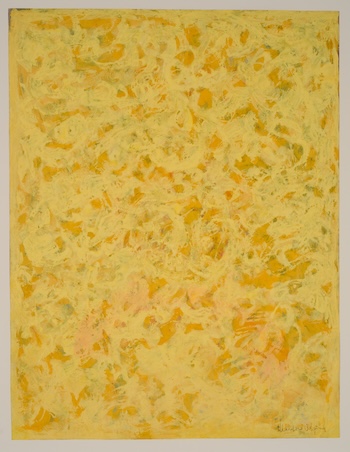

Beauford Delaney, Untitled, 1960. Watercolor and gouache on paper. Photo: The Drawing Center, NYC

Notably, even as he energetically pursued abstraction Delaney did not leave portraiture behind. Rather, he provocatively blends the two. Four self-portraits from this period (1962 through 1970) show an artist confident enough to reimagine representation by drawing on a non-representational toolkit. The viewer peers into these self-portraits and Delaney peers back. Gone are the conventions of studious representation; this is the portrait made anew.

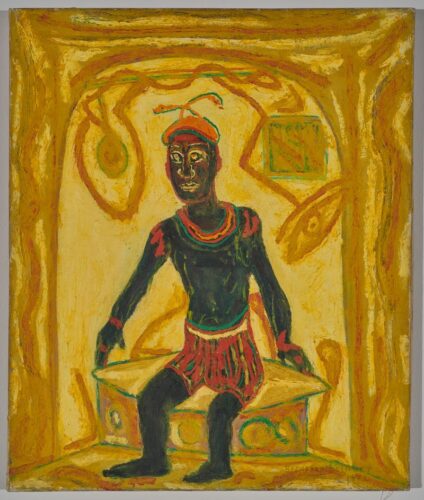

Beauford Delaney, Self-Portrait in a Paris Bath House, 1971

Oil on canvas. Photo: The Drawing Center, NYC

The latest dated work in the show—Self-Portrait in Paris Bath House (1971)—serves as a fitting culmination, and not only because it is the last self-portrait Delaney is believed to have painted. In this picture, he presents his full body — the only known self-portrait where he does so — and conveys his vulnerability. Trapped in a kind of box, Delaney displays his 70-year old self, sitting and leaning slightly backward, his hands gripping the edge of something, as if lounging or perhaps trying to get as far away from the viewer as possible. His eyes burn bright, seeming to project light. It is as if he is affirming his independence from his surroundings or maybe something greater. In this picture, Delaney explores his queer identity, in addition to his own African heritage (his clothing is said to resemble that of a Maasai warrior). The biographical cues are evident, but he deftly deploys the plastic qualities of art — color, line, and the illusion of depth — without wasted paint or brushstrokes to set out his story.

The constraints of portrait painting have provided artists with opportunities to experiment since the dawn of modern art. As modernists before him, Delaney pushes against while remaining within the limitations of the medium. Delaney’s late portraits are more distilled than his earlier ones. They can appear less true to life, but also come off as more truthful. At The Drawing Center, we are given a Delaney who is representative of Blackness, queerness, and neurodiversity. His approach to painting offers essential object lessons in finding freedom, proving that abstraction can both derive from and enhance representative art.

Helen Miller is an artist. She teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Harvard Summer School. Michael Strand is a professor in Sociology at Brandeis University.